What we learn from screenwriting

Writing screenplays is a very good discipline for other forms of

writing. You have to get off the mark quickly with a screenplay: you

don’t have fifty pages to introduce your characters and setting and lay

out the tracks of your story. If you haven’t hooked your audience within

the first ten minutes, you’ve almost certainly lost them. I’ve seen a

lot of blogs on FB and other such platforms that seem to treat the

structural model for screenplays as a kind of universal template for

creative writing: hook the audience, introduce the main characters, get

to the 1st Act climax, then on into complications and reversals of

fortune in the 2nd Act, before arriving at the climax which leads into

the denouement and resolution of all problems in the 3rd Act.

All well and good. Or is it? The model fits the screenplay so well that

many may be unaware that it doesn’t really suit other forms of writing

with the same degree of snugness. Our lack of awareness may partly stem

from how much time we set aside for the different (and often competing)

forms of entertainment available to us in the 21st century. It’s a

no-brainer that more people watch films and box-sets of series on TV

than read the novels of Trollope or Dickens. If I read a Dickens novel

it usually takes me a month or three, whereas I can watch even a fairly

longish film in 2 – 3 hours.

The novel format is more akin to symphonic music with its various

movements, slow or lively, and its carrying over of thematic material by

way of recurring leitmotivs and tropes. The novel has, to a large

degree, suffered with the rise of film as both a commercial and artistic

entity. I think it’s fair to say that cinema is one of the greatest

achievements of the twentieth century. Yet, if we look back to the early

days of cinema, film didn’t seem then to have the depth and resonance

of the novel. Take a look at the year 1916, for a comparison of the best

that cinema was putting out to the public and, on the other hand, what

novelists were creating. On December 29, 1916, James Joyce’s A Portrait

of the Artist as a Young Man was published -a ground breaking work of

Modernism, taking us into the heart and soul of the protagonist Stephen

Dedalus. By contrast, D. W. Griffith released Intolerance which at just

over 2.5 hours isn’t the most indulgent of silent movies. But it relies

almost entirely on its spectacular sets and lavish design. I doubt very

much whether a viewer of today would be able to digest it all at one go.

He or she might be able to take it in on a DVD in manageable bites. But

it would still be a hard sell to anyone below the age of fifty!

So, look back now to the opening sentence of this blog. Why do I say

that writing screenplays is a very good discipline? I say this because

once film studios had adapted to sound, and actors became comfortable

with a naturalistic style in front of the camera, then a different sort

of movie emerged that began to match (in its own way) what novels had

been doing for the previous two centuries. There was a creative

blossoming that brought great screenplays to Hollywood and captured the

imagination and hearts of millions. And writers did this by creating

scenes that made a host of total strangers sitting in darkened rooms

feel the anguish and pain or deep joy of the heroes and heroines in

their stories. This is why we write: through empathy to reach out to

others, complete strangers, and make them burn with a passion to see

justice done, to have a wrong righted, to see love triumph and evil cast

down.

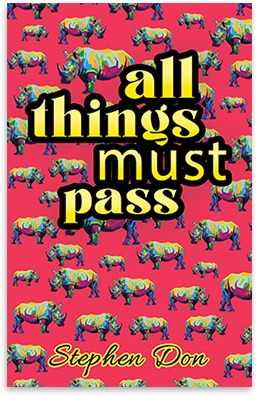

I had my first novel (all things must pass) published in late October

2021. The curious history of this piece is that the first part of it was

written as long ago as 2005. In 2019 I had this first part published as

a kind of chapbook and showed this to two very good friends of mine.

Thankfully, they both liked it very much and encouraged me to continue

the story and make it a novel. I hadn’t really considered doing this

until this point. What I had been doing in the intervening years between

2005 and 2019 was writing short film scripts and a couple of

feature-length scripts. In September 2019 I won an Empire Award for The

Last Days of John Wilkes Booth at the New York Screenplay Contest. So, I

had been making progress in my screenwriting and it was the hard graft

that I had put into these screenplays that came to my aid as I turned to

consider extending the story that would eventually become my first

novel.

It’s hard coming back cold to a piece of writing that you let go of

nearly a decade and a half ago. But I had two things to fall back on to

crank the old motor into motion: my own life experiences and the

experience of writing scene after scene in screenplays. I knew I had to

take my protagonist, Martin Wilson, into new territory and challenge him

if he was going to be able to change and adapt and move the story

forward. This is what happens to us in life: we move from the family

home and we have to make a life for ourselves. It isn’t ever

straightforward and simple. There are setbacks and complications, just

as in a story. So, I had an overarching trajectory for Martin’s story

and as I read and re-read that long short story which would become the

first part of the novel, I began to dimly see how the story could

progress.

But here one of the great differences between novel writing and

screenwriting starts to reveal itself. Unlike in a screenplay, where you

can sketch out virtually every scene before you write a word of

dialogue, the scenes in a novel can be of such varying length and

contain such a wealth of ideas that you never really have quite the same

degree of control over where the novel is heading as you do with a

screenplay. You can get so surprised about the direction that your novel

is taking that you may wonder from which part of your subconscious a

particular character or sequence of images emerged. The thing is that

with a novel you (the writer) are everything: director, cameraman,

actors, and puppet master! In a screenplay you mustn’t describe the

scene in too much detail. That glorious sunset you spend half an hour

creating may be washed out in a thunderstorm as the cameras turn over. I

can see Bogie standing in front of a fireplace as he talks to Brigid

O’Shaughnessy in The Masltese Falcon, but don’t ask me to give a

detailed description of the room.

Perhaps the greatest bit of advice to writers was given by Aristotle

nearly 2,500 years ago: a story has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

You can have a rush of inspiration and be like a momentary maniac or

drunkard trying to get that beginning down on paper (or into your

computer). But once that rush of inspiration has left you (and it always

does!) then you have to fall back on hard graft and a knowledge of

structure -what scenes are meaningful, what scenes push the story

forward? This is where screenwriting can be of great assistance. There

is no room in a screenplay for pretty scenes that do not support and

advance the story. As one of the greatest novelists of the twentieth

century (William Faulkner) is reputed to have said: “You must kill your

darlings.” In other words, you may have written a purple passage of

prose but if it jars with the rest of the story or indeed impedes that

story -cut it out! It is surely no accident that Faulkner worked in

Hollywood for a number of years as a screenwriter.

Post Views : 352